by Jeff Jardine • Modesto Bee • September 22, 2005

This ultimately becomes the story of a Hurricane Katrina evacuee who experienced kindness and help — firsthand, so to speak — from two local doctors and a hospital in Modesto.

This ultimately becomes the story of a Hurricane Katrina evacuee who experienced kindness and help — firsthand, so to speak — from two local doctors and a hospital in Modesto.

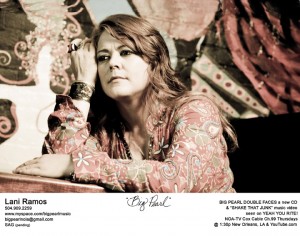

First, though, you have to understand what brought Lani Ramos here.

From the moment Ramos set foot in New Orleans six years ago, she embraced the city’s soul and culture of “laissez les bon temps rouler.”

That, for those who don’t understand French or have never been to the Big Easy, translates to “let the good times roll.”

“I fell in love with New Orleans,” said the 35-year-old singer, guitarist and songwriter whose parents, Ben and Lorrie Ramos, have lived in Modesto since 1989.

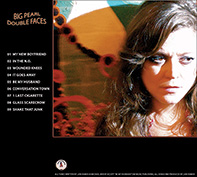

She made an impact on New Orleans as well. Ramos and her rock band, Big Pearl, got solid reviews on Web sites such as bestofneworleans.com. She began recording and earned gigs at clubs throughout the city, including world-renowned Tipatina’s. She sang with the legendary Fats Domino.

Things were going so perfect that something was going to have to go wrong,” she said. “And that’s what happened.”

That something was Hurricane Katrina. When it bore down last month, Ramos left her two-level apartment on Bourbon Street in the famed French Quarter. She holed up with friends in the opulent Bourbon Orleans Hotel a few blocks away to ride out the storm.

“We’d had so many scares before,” Ramos said. “We thought it was going to be just another story of ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf.’ We thought we’d go right back to what we were doing.”

The 150 or so fortunate ones inside the thick-walled, 188-year-old hotel building simply did what they do best in New Orleans. They partied. They enjoyed gourmet meals. They played music and sang. And they were oblivious to the devastation the hurricane and the weakened levee system were about to wreak upon the city.

Ramos held a wine glass in her hand when power went out and the hotel went dark Aug. 29. Pitch black. As she groped her way through the darkness, she walked straight into a wall, crushing the goblet between her left hand and chest.

The broken glass cut into her chest, causing some bloody, albeit minor wounds. Worse, it severed tendons in the middle finger of her left hand. That’s a real problem for a guitar player. But the finger would have to wait.

She faced a more immediate problem: Getting the heck out of New Orleans as the flooding, turmoil and hysteria began.

Ramos stayed long enough to guide a Houston Chronicle reporter to the St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square, where a statue of Jesus stood virtually unscathed among downed trees.

“He was basically unhurt,” she said.

Then she left New Orleans, crossing the Mississippi River into Algiers before deciding she’d be better off back at her Bourbon Street digs because the French Quarter sits on high ground and wouldn’t flood.

Law enforcement officials refused to let her return.

“They had declared martial law,” she said.

Ramos’ 1985 Mercedes station wagon was desperately low on gas and the stations were all closed. Street lights out, she took to the darkened roads the night of the 31st.

She drove north, scared and alone, but caught a break when a small-town sheriff gave her three gallons of gas. Then a National Guard officer gave her two gallons more. She made it to Baton Rouge, on to Lafayette and eventually to the safety of friends in Crystal Beach, Texas, a city now being evacuated as Hurricane Rita approaches.

Ramos flew to California, spending a few days in San Francisco before arriving in Modesto on Sept. 11 to stay with her parents. She visited the county’s Health Services Agency to see what could be done about her damaged digit.

Ramos flew to California, spending a few days in San Francisco before arriving in Modesto on Sept. 11 to stay with her parents. She visited the county’s Health Services Agency to see what could be done about her damaged digit.

As a single woman and a musician, she is among the uninsured. Yet here, she found people who wanted to do their part for Hurricane Katrina victims, even though she admittedly had it better than most during the storm.

Tuesday morning, a health official referred Ramos to the Golden Valley Health Center in Modesto, where she saw Dr. Vikram Khanna and told him about her Katrina experience.

Khanna knew she’d need surgery to resume her musical career. He made some phone calls, looking for a surgeon who would do the operation for free. Dr. Paul Caviale stepped up, and Doctors Medical Center donated the use of an operating room.

“The big question was would he even be able to help her at this point?” Khanna said.

That same evening, Caviale performed a 90-minute procedure to fix her finger.

“She’s had it cut for about two weeks,” Caviale said. “It was good to get it done before it went too much longer. She’ll be able to play the guitar again.”

Ramos affectionately calls Khanna “Dr. Karma” and Caviale “Dr. Cavalier.”

“They’ve been just wonderful to me,” she said. “It all came together so fast.”

She’ll need time to heal and rehabilitate the finger before resuming her career, wherever that might be. Many New Orleans musicians, Ramos said, are showing up at clubs in cities like San Francisco, uncertain whether they’ll ever return to Louisiana.

“I want to say I’ll go back,” she said.

As the song lyrics go, she knows “… what it means to miss New Orleans.”

But unlike her surgically repaired finger, Ramos knows the city will never be the same.

Since she began singing in choirs and talent shows at the age of seven Lani’s journey to the Blue Nile has included Puerto Rico, Los Angeles, India, San Francisco and New Orleans, holding virtually every job in the entertainment industry along the way. Her desire to be an actress at an early age took her to Los Angeles where she turned a gig in the mailroom at 20th Century Fox into five years of production work in music, TV, and film. It eventually became clear to everyone that Lani’s booming voice, and larger than life personality could not be contained behind a desk. She left L.A., traveled to India, and upon returning bought a one-way ticket to the Crescent City, arriving on her birthday in 1999. “My first week here changed my whole life,” says Ramos, which included an unbelievable chance to meet and sing for Fats Domino, a day that Ramos still draws inspiration from. Her love for New Orleans hasn’t changed, despite having suffered serious illness from living with black mold and relocating to San Francisco for a short while after Katrina, “The feeling of freedom in New Orleans is amazing, but really I chose to stay here for the people, that real feeling of township, you can’t get that anywhere else.”

Since she began singing in choirs and talent shows at the age of seven Lani’s journey to the Blue Nile has included Puerto Rico, Los Angeles, India, San Francisco and New Orleans, holding virtually every job in the entertainment industry along the way. Her desire to be an actress at an early age took her to Los Angeles where she turned a gig in the mailroom at 20th Century Fox into five years of production work in music, TV, and film. It eventually became clear to everyone that Lani’s booming voice, and larger than life personality could not be contained behind a desk. She left L.A., traveled to India, and upon returning bought a one-way ticket to the Crescent City, arriving on her birthday in 1999. “My first week here changed my whole life,” says Ramos, which included an unbelievable chance to meet and sing for Fats Domino, a day that Ramos still draws inspiration from. Her love for New Orleans hasn’t changed, despite having suffered serious illness from living with black mold and relocating to San Francisco for a short while after Katrina, “The feeling of freedom in New Orleans is amazing, but really I chose to stay here for the people, that real feeling of township, you can’t get that anywhere else.” Ask anyone who has had the privilege of playing with Lani and they will tell you despite her hilarious personality she is extremely dedicated, disciplined, and professional – something she credits to growing up an athlete and years of working in L.A. studios, “getting her butt kicked.” Lani admits that “To be a successful singer you have to learn to be very humble and self-absorbed at the same time.” Her advice for next generation of rock chicks trying to make it in New Orleans – “practice, practice, practice!” “You’ll get more recognition through practice than any promotion or advertising,” she says, “Always stick to your own standards and convictions. Don’t let others bring you down. Keep beating your own drum and stay positive!” Lani keeps herself centered by having a having a close relationship with God and having spent a lot of time in the St. Aug choir, kitchen, and gardens. Ramos’s current work in the community also includes being an advocate for information on black mold and organizing a Memorial Day weekend second line for all EMT’s and First Responders to Katrina and the B.P. oil spill.

Ask anyone who has had the privilege of playing with Lani and they will tell you despite her hilarious personality she is extremely dedicated, disciplined, and professional – something she credits to growing up an athlete and years of working in L.A. studios, “getting her butt kicked.” Lani admits that “To be a successful singer you have to learn to be very humble and self-absorbed at the same time.” Her advice for next generation of rock chicks trying to make it in New Orleans – “practice, practice, practice!” “You’ll get more recognition through practice than any promotion or advertising,” she says, “Always stick to your own standards and convictions. Don’t let others bring you down. Keep beating your own drum and stay positive!” Lani keeps herself centered by having a having a close relationship with God and having spent a lot of time in the St. Aug choir, kitchen, and gardens. Ramos’s current work in the community also includes being an advocate for information on black mold and organizing a Memorial Day weekend second line for all EMT’s and First Responders to Katrina and the B.P. oil spill.

This ultimately becomes the story of a Hurricane Katrina evacuee who experienced kindness and help — firsthand, so to speak — from two local doctors and a hospital in Modesto.

This ultimately becomes the story of a Hurricane Katrina evacuee who experienced kindness and help — firsthand, so to speak — from two local doctors and a hospital in Modesto. Ramos flew to California, spending a few days in San Francisco before arriving in Modesto on Sept. 11 to stay with her parents. She visited the county’s Health Services Agency to see what could be done about her damaged digit.

Ramos flew to California, spending a few days in San Francisco before arriving in Modesto on Sept. 11 to stay with her parents. She visited the county’s Health Services Agency to see what could be done about her damaged digit.